Inside Coach Kroh’s Classroom and Legacy

May 3, 2022

What is often invisible to those who experienced Kroh’s influence on St. X indirectly is what lies at the core of his mission: a simple yet boundlessly powerful principle fundamental to his professional success and uniqueness.

***

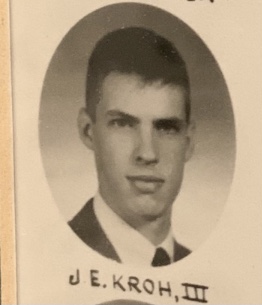

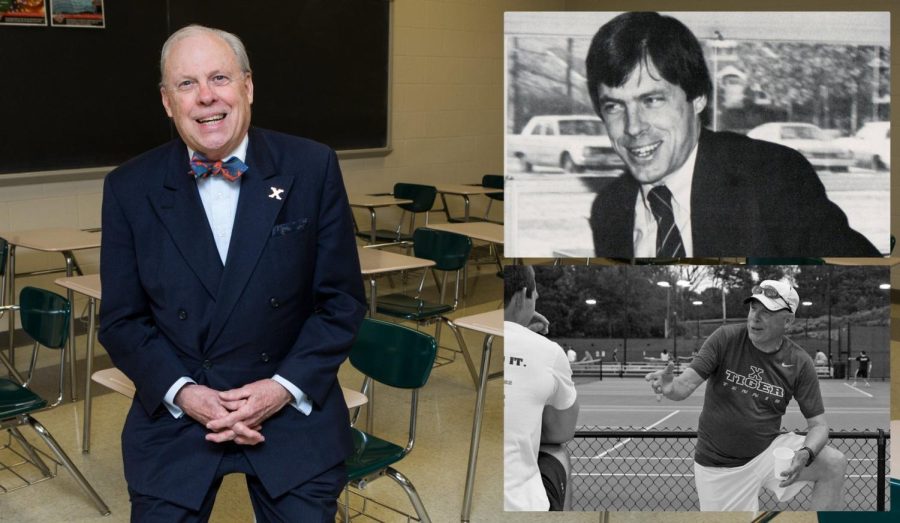

More than just an educator, coach, athlete, and writer, Mr. Kroh was a custodian of Xaverian values whose excellence extended across all facets of his unprecedented 54 year career. His arrival at 118 West Broadway in 1957, through his ignorance, marked the advent of a new era of Xavierian education. The last class to graduate on West Broadway, Kroh would return to St. X eleven years later with fresh ideas, knowledge, and perspectives to accompany a correspondingly new campus on Poplar Level Road. Kroh’s unorthodox, philosophical teaching style forged his notoriously challenging English class into an unforgettable experience for over 6,000 Tigers, changing the way his students think forever.

Kroh is one the few paradigms of Xavierian excellence who’s virtuosity extends across multiple facets of the St. X experience: as a student, teacher, and coach. After winning the 1957 basketball City Championship as a freshman, he went on to set a Kentucky state record in the mile race in 1960, making him a KHSAA Cross-Country champion for the second consecutive year. In 1961 Kroh became the first Kentucky prep runner to break the ten minute mark on his two mile race, earning him a full athletic scholarship to Seton Hall University. Like so many Tiger student-athletes, Kroh’s incredible diligence allowed him to maintain a GPA of above 3.5, all whilst competing in the National Cross Country Championships in Madison Square Garden during his collegiate years.

The KHSAA Hall of Fame inductee would later bring his remarkable collegiate experience back to Poplar Level Road after a meeting with Brother Conrad Callahan in the spring of 1968. The rest is history.

“I tried to model my teaching after the Xavierian Brothers, who I thought were always ‘out there’. They were unique, interesting and, above all, unafraid. Those are things I tried to be.”

What separates Mr. Kroh as an educator is his willingness and unyielding bravery to create his own path. A man who sought the road less traveled, he took the remarks of his teaching style being “out there” as a compliment, although it wasn’t often wasn’t intended as such. Kroh wasn’t afraid to break down traditional rules of teaching and define his own boundaries. He created a bipartisan classroom environment in which his students were expected to hold him to the same expectations that they themselves had to follow.

As a former student of his class, I can attest to my confusion on the first day of school seeing a paper labeled “Senior Rights” on my desk. Not that I wasn’t used to receiving a long list of rules and guidelines on the initial day of a class, as I had in every class previous to Mr. Kroh’s, but rather shocked to see expectations directed towards my teacher rather than myself. Some of the ten listed included: “Seniors have a right to expect a teacher who shows up every day prepared to give the best that he has,” and, “Seniors have a right to be treated as the adults they are becoming, not to be coddled or treated like children.” Mr. Kroh set a clear, sui generis tone, a message of duality that separates Kroh from other educators and has elevated him onto the Mount Rushmore of St. X: If I can expect the best from my students, they can expect the very best from me.

“(My favorite moments) always involve seeing the guys ‘get it’, when the light comes on, and they begin to see clearly how to take charge of things by themselves.”

1,000 track and field meets and tennis matches, 10,000 school days, 50,000 classes, and 300,000 essays, quizzes and tests graded – none of it matters if his students didn’t “get it.”

There was an intricate, carefully organized method behind the madness of Kroh, although at first only the madness seemed to be noticed. The rumors of this madness, pervasive among the halls of St. X and outright frightening in detail, left seniors holding their breath walking through Kroh’s door in August, savoring their last moments of freedom before, supposedly, being bogged down by hours of homework every night and miserably failing the impossible quizzes they had been warned about by the previous graduating class. I was one of them. Unnerved and apprehensive, I sat down in ignorance of the journey that was before me.

After limping my way through arduous essays and thrice weekly quizzes, or “reveals” – he would call them – I realized that this class was just as difficult as the seniors before me claimed it to be, however, I also began to grasp a concept much deeper and more intricate than the strenuous work Kroh seemingly loved to assign. Kroh didn’t design his often taxing curriculum to make his students progress as writers, readers, and speakers so much as he did to see his students progress as men: men who take charge of their own education, life aspirations, and drive to succeed. His eccentric, mentally strenuous, and sometimes outright frustrating manner of teaching created an environment in which it was imperative for his students to discover their will to succeed from within themselves, rather than being fed such inspiration via pressure from teachers, parents or coaches. A parent renders useless when studying for a test in which there is no study guide, outline, or even direction in which to scan and study. A student’s keenness to learn, participate, and understand during class time is left alone to measure their readiness for an upcoming “reveal”; hence his renaming of the word “test”, as his tests simply revealed a student’s true eagerness to succeed. Kroh’s focus on the ego of the student encouraged his seniors to have conversations with themselves asking why they are there, what motivates them to succeed, and, therefore, how they can take charge of their own education, as only a settled mind on that which is necessary to accomplish can succeed in Kroh’s class.

“Four axioms of this class that people know who have taken charge of their own education: 1. We are not God. So we can only be here. Or there. 2. It’s all true. Unless it isn’t. 3. It’s all good. Until it’s not. 4. There is nothing one human being will not do for another. There is also nothing one human being will not do to another. There is always a choice.”

Memorized by heart for all those who’ve had the pleasure of being taught by Coach Kroh, the four axioms are the keys to finding the answer for the question Kroh’s class proposes: “How do I take charge of my own education?” Four rules that suggest they were written by Socrates at first glance, are rather ambiguous in their purpose and place in a classroom. This is by design. The enigmaticness of the axioms allows students to put their own imagination and circumstances into the meaning of the words, conforming them to rules of life rather than merely academic guidelines.

All four are individually important in their own context, however, the first of the axioms specifically changed my way of thinking for good: “We can only be here. Or there.” I’ve interpreted “here” to be our present, physical world, a world in which the five senses translate into reality, and “there” as a theoretical world, a world not real, only imagined or predicted. The contradicting realities of these worlds, one being “real” and one not, doesn’t allow someone to be present in both simultaneously. In other words, Kroh tells us that if we choose to spend our valuable time in the future, you are forfeiting your current space in reality. I took this to be a little more than Kroh simply trying to tell us to pay attention to his lectures, but rather as a secret to taking charge so simple that it must be true. By readverting my consciousness from the hoped, dreaded, and imagined to my contemporary environment, I have successfully taken charge, and therefore have conquered Kroh’s class by cracking the paramount principle behind his unorthodox, philosophical way of teaching.

It’s all so simple and so true… unless it isn’t.