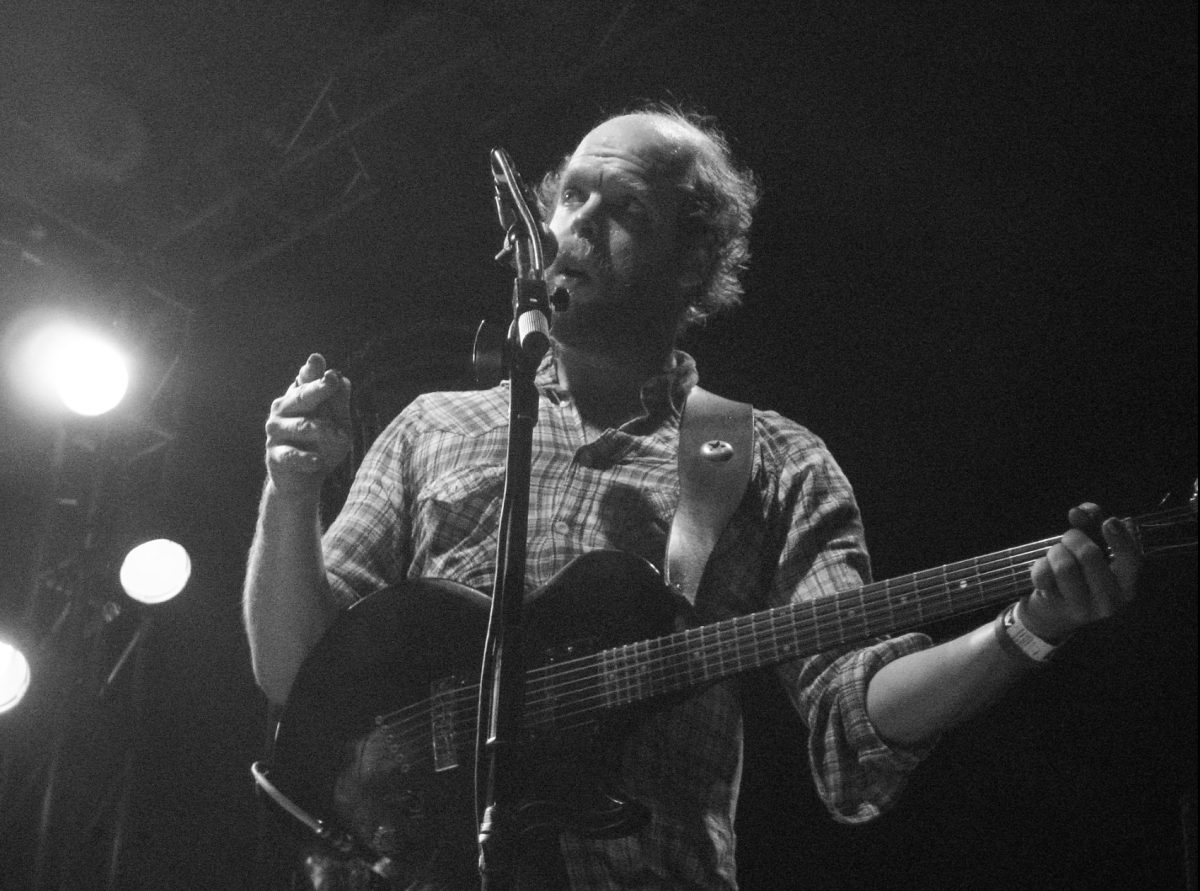

Will Oldham is hard to pin down.

He stays quiet considering how much he does publicly. One day he’s scoring weird arthouse films, or voice acting for an array of Adult Swim shows, the next he’s biking around Louisville and playing at independent local shows. This guy’s a Louisville icon, a cult superhero, and probably the only musician alive who could casually vanish from the ever-present eye of the media and reappear with a handwritten record that he pressed in a friend of a friend’s basement.

In the 90s, during the creative peak of Louisville’s indie music scene, Will Oldham began releasing music under the moniker Palace Brothers, working alongside members of the legendary rock band Slint. Over the years, he’s become a pillar of not just Louisville’s music scene, but indie music worldwide.

Oldham continued putting out records under variations of the Palace name—Palace Brothers, Palace Music, Palace Songs—until he eventually parted ways with Drag City Records and iconic punk producer Steve Albini. From there, he started his own label (also named Palace) and began releasing the first of many records that would cement his reputation as one of indie music’s most compelling and unpredictable figures.

Nearly everything he’s made has been met with critical acclaim, but his most well-known and revered album is I See a Darkness (1999). The title track alone has been covered by the likes of Johnny Cash and Rosalía. Pitchfork even gave it a rare perfect score. And personally? I think it lives up to the hype.

Beyond music, Oldham has dipped into acting, starring in films like Old Joy (a cult favorite in the Criterion Collection) and making cameos in others, like A Ghost Story, where he played a mysterious prognosticator. His career has been anything but predictable.

In short, Will Oldham is a big deal—both to Louisville and to artists everywhere.

Originally, I set out to write a story about Louisville’s music scene—how chaotic, influential, and downright weird it can be. And when I thought about who to reach out to for an interview, Oldham was one of the first names that popped into my head.

However, a quick note about trying to interview Will Oldham: it’s unpredictable.

He is not the type to do a traditional press cycle. He famously is quiet and evasive during interviews. It is very rare that he offers a glimpse of what he’s like. He’ll talk to you when he feels like it, and when he doesn’t… you’ll wait.

I didn’t hold my breath for a response. He had just dropped a new album, announced tours across Europe and the East Coast, and he’s got a kid. Plus, with how prolific he is, I figured he was already onto his next project. He’s busy.

But to my surprise, he replied. Said he was down to talk. We set up a time. I prepped. I waited.

And then… nothing. No email, no text, no call.

Then, out of nowhere, he sends me a simple five-word excuse for his absence:

“We were at circus practice.”

Circus practice.

I don’t think I’ve ever gotten a more perfectly in-character reason in my life. But with it came a question about my deadline—proof that he was still down to talk. We rescheduled. 80/20 at Kaelin’s kindly let us record there.

We sat down, got to talking, and ended up speaking for so long that the restaurant closed mid-interview. The following are the most interesting questions from my two-hour interview with him.

——————

Josh: I first found out about you and your work through Old Joy. I really related to your character—he’s just this untethered, unmoored drifter. That connection led me to your music in the first place. After all these years, do you still feel any connection to Kurt?

Will Oldham: I think it probably helped me get it out of my system. Yeah. I don’t— I mean… you know, maybe, who knows? Maybe he could turn it around somehow, but it doesn’t seem like it.

Josh: Um, while I was doing research for this, I saw that you were listed as a member of Silver Jews at one point. This question is barely even for the interview—it’s more for me. I like listening to all the Silver Jews records, and I was like, man, I don’t really hear you on them— at least I didn’t hear you singing. Were you playing guitar or something?

Will: Yeah. On one of the records, for some reason, David asked me to play guitar, which I thought was really interesting. Yeah, I played guitar, sure, but I never really thought of myself as a guitar player. I always saw myself more as a singer. But David was just like, “No, I want you to be my guitar.”

—————————

At this point we were about fifteen minutes into the interview, and he was being his usual self. Quiet one-word responses, nods in agreement, grunts of acknowledgement. I cut out a lot of content before this point because it was all shoulder-shrugging filler. I had to take a risk and ask something disarming but weird enough to capture his interest.

—————————

Josh: So, you’re in a white room, and you have to fight either ten baby-sized monkeys or ten monkey-sized babies. Which one do you choose?

Will: It’s— No, okay… So monkeys… babies… I have to fight a monkey or a baby. Ten little monkeys or ten big babies. Is that what you’re asking?

Josh: Yeah. Monkey-sized babies or baby-sized monkeys.

Will: And I have to fight them? Like… kill them?

Josh: Whoa, no! Not to kill them, but you gotta fight. You have to win.

Will: But what is winning? It’s interpretive. What would you do?

Josh: Morally, I’d have to fight the monkeys, right?

Will: What, because you don’t think monkeys have value?

Josh: Okay, fine, they do have value, but I can’t just beat up babies.

Will: So you have to fight them? You could fight them verbally. You could fight them with math problems. You could do a potato sack race. In which case, I’d probably choose the monkeys because it would be funnier.

Josh: Okay, but let’s say it’s just you in a room, no rules, no alternative competitions—how do you approach it? Which one do you take on?

Will: I’d rather be in a room with ten monkeys than ten babies. The babies are huge. Also, what kind of monkey are we talking about? A gorilla? A spider monkey? A monkey-sized baby could be a tiny preemie baby that should be in an incubator. There are a lot of monkeys out there.

Josh: I’m thinking a variety pack—you get a little bit of everything.

Will: Uh-huh… I don’t know. I’d still rather be with ten monkeys. Babies aren’t that interesting to me.

Josh: Yeah, but they’re easy to fight.

Will: How do they fight? Anyway, look, Josh, if this gets physical—monkeys will tear off your face. Babies… they wouldn’t put up much of a fight.

Josh: No, they wouldn’t. But they’re huge. And do you think you could really do it? Beat up a baby, I mean.

Will: But if I had ten monkey-sized babies, here’s what I’d do: I’d stand up and say, “I win.” And it’s over.

Josh: Whoa.

Will: Right?

Josh: I don’t think that’s allowed. I think you just broke the rules.

Will: Well, you haven’t told me the rules. I might just go like this— *he taps my hand*— “I win.” What are they gonna do? Babies can’t surrender. Monkeys can’t either. They don’t have as developed a sense of fighting as you and I. So are we knocking them unconscious? Holding them down? Killing them?

Josh: That’s a little much…

Will: Well, what’s the sign of victory?

Josh: You’re right. I didn’t think this through. I’ve been talking about this for hours and didn’t consider any of this. This is why you’re such a fantastic mind.

Will: I don’t think so.

Josh: Why not?

Will: Because all I did was try to understand what you meant by fighting ten monkey-sized babies.

Josh: I’m just baffled. You brought like a hundred new points to the table.

Will: That’s my job.

————————

Alright, enough baby/monkeying around. It was at about this point he started to really talk, I think. This social armor that he wore just started to splinter and fall off, and we sat in that booth for another hour and a half. The restaurant closed before we completed our interview and we were still speaking as we both walked out.

————————

Josh: So, here’s a question about Louisville. Do you still feel connected to the city? You’ve worked with a lot of the big artists here—how much of an influence do you think that has on your music?

Will: Yeah, I mean, it’s a big influence. Two of the last three Bonnie “Prince” Billy records were made in Louisville with all Louisville musicians, and the next one is going to be made here as well—with all Louisville musicians. So yeah, it’s crucial.

Josh: That’s sweet.

Will: Yeah. I mean, I like to think of place and community as vital—not just in life, but as actual content for the things we create. When you work with people in your own community, you build a greater depth of relationship, and hopefully, that translates into the work. Ideally, it reaches deeper places in the audience than it would if it was just, you know, some joker in Brooklyn.

Josh: Right, just another person saying, “Hey, I’m in New York, trying to make it.”

Will: Exactly. Who cares? There are thousands, maybe tens of thousands, doing the same thing. But when it’s tied to something real—something rooted—it matters more.

Josh: I’ve never seen you live, but I was wondering—what’s the difference for you between performing and recording? I know that’s kind of a vague question, but like… with performing, you actually see something, whereas with recording, it’s just audio. Does that change the way you present your music?

Will: I think they’re almost completely unrelated.

Josh: Oh yeah?

Will: The industry connects them, so I do both. But to me, recording is about capturing the essence of a song and a lyric in such a way that it can be listened to in a variety of atmospheres and landscapes. You want the lyrics to be clear because there’s nothing else—it’s just audio.

Live performance, on the other hand, is about picking up on the energy of the people in the room and creating a musical, emotional bond in the moment—something unrepeatable. A recording, though, can be repeated infinitely. So yeah, they feel like completely different mediums.

Josh: But you still sing in both.

Will: Yeah, I sing in both, but beyond that, there’s not much to connect them. That said, playing live helps sell records, and making records helps people become aware that the music exists in the first place.

Josh: So, I wonder—are you the kind of artist who’s super particular about how things go in the studio? Like, David Lynch had this very specific way he wants his movies made. Is your recording process more orchestrated, or is it freer? Basically, when you’re in the studio, are you really particular about how it all goes down?

Will: Yeah, I don’t—I mean, I kind of question everything. You know, a lot of people go into a recording studio and just think, “Okay, this is what you do.” They sit where they’re told, use the mic they’re given, and do it how they’re told to do it.

But I always ask, why? Why do I have to go in that room? Why not sit here instead? Why use that microphone? Why not this one?

And if the answer is just, “Oh, well, that’s what the last person did,” then I start thinking—are we making the same record they were making? Because I don’t think we are. This is a new record. So let’s approach it like it’s its own thing. It just doesn’t make any sense to do it otherwise. It’s art—you’re supposed to be creative. You’re supposed to approach it like the piece has its own life, its own will. But a lot of people walk into the studio like they’re entering a morgue. Like, the record’s already dead. And it’s like—wait, what? It’s not dead yet. Are we here to kill it? Can we kill it here?

Josh: Circus practice? What’s that all about? What do you do with them?

Will: Turner’s Circus. My daughter and I are performing in it tonight and tomorrow night. It’s awesome. You should go some time. It’s every year around this time.

Josh: I recently discovered Joanna Newsom’s music— big fan, huge fan— and there’s a legend about you giving her mixtape or something to Drag City. Is this true?

Will: In the early 2000s there was a fellow named Bobby Birdman who was playing keys in the Bonny band, and he’s from Nevada City, California. We played a show there at the end of a tour, and the next morning he gives me a CDR containing the music of a friend of his: Joanna. And it was quite compelling. I listened to it for about a year, then asked her to come on a tour as the opening act, then foisted her onto Drag City.